The popular weight loss drug Wegovy seems to provide more health benefits for people who have diabetes and a common kind of heart failure than just helping take off the pounds, according to a new study.

The study, published Saturday in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed how the drug helped people with Type 2 diabetes who also had one of the most common kind of heart failure, obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. This condition happens when the heart pumps regularly but is too stiff to fill properly.

Current treatment for this condition involves lifestyle changes and heart medications, but there are no therapies specifically approved to treat this particular condition, and the number of people who have it has been growing significantly, the study authors said.

Obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction can severely limit a person’s ability to participate in the activities of daily life. They often become tired easily and they have trouble breathing, and the condition can carry a high risk of hospitalization, disability and death.

Often, people with type 2 diabetes who have this kind of heart failure have a more severe form than those who don’t have diabetes.

The researchers who conducted this study – which was funded by the drug’s maker, Novo Nordisk – also published one last fall that found that Wegovy had significant positive health effects for people without diabetes who had this heart condition. But because people with diabetes may respond differently to medication, they wanted to learn whether they might see similar results in this additional group.

People with a more severe form of heart failure sometimes don’t respond as well to medication as those with less severe disease. Weight loss studies have also found that people with diabetes who took Wegovy tended to lose weight, but it wasn’t as much as those who did not have diabetes.

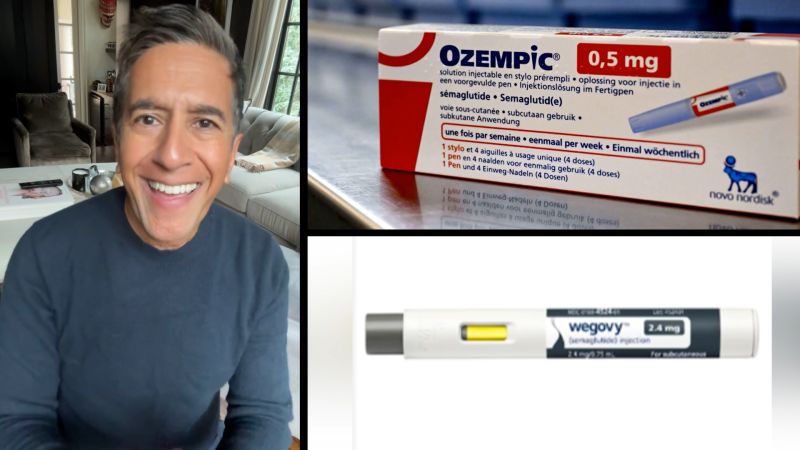

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved two injectable semaglutide medications, which mimic the body’s GLP-1 hormone to help with insulin production and signal the brain to reduce appetite. Ozempic was approved in 2017 for type 2 diabetes, and Wegovy was approved in 2021 for obesity. In March, the FDA also approved Wegovy to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack and stroke in adults with cardiovascular disease and either obesity or overweight.

The new research seemed to offer further proof that Wegovy’s benefits extend to people with diabetes.

For this study, the researchers randomly assigned 616 people who had type 2 diabetes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction into two groups. The participants came from 108 sites in 16 countries and Asia, Europe and North and South America, and all had a body-mass index of 30 or more. One group got Wegovy, and the other group got a placebo.

The participants who got Wegovy started at a lower dose and built up to a 2.4 milligram dose once a week. Researchers followed both groups for a year.

The people who got Wegovy had much better outcomes, with more weight loss and a bigger reduction in heart failure-related symptoms and physical limitations compared with those who got the placebo.

They also could walk farther over the course of six minutes and had improvements in biomarkers for inflammation and other problems.

The group treated with Wegovy had fewer adverse events like hospitalizations and urgent doctor visits, although the number of events was small in both groups.

There were 55 serious adverse events reported in the group that took Wegovy and 88 in the placebo group. Six people died in the Wegovy group during the study period, compared with 10 in the other group. One death in the Wegovy group and four in the placebo group were related to cardiovascular issues.

The consistent positive results from this trial and the one published last year seem to suggest that Wegovy is an effective and safe treatment for a broad population of people, including those with diabetes, said study co-author Dr. Mikhail Kosiborod, a cardiologist and vice president of research at St. Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Missouri.

One of the most common questions he received after last year’s study came out was whether he thought the weight loss had the biggest positive impact on people with heart failure. But the new research may show otherwise, he said.

“I think the answer from the trial clearly suggests that, while weight loss is likely an important factor, it cannot explain everything,” Kosiborod said.

If people with diabetes lost 40% less weight on the drug than similar heart patients without diabetes, one may expect to see 40% less benefit, he said, but the positive benefits were actually about the same.

“I think that’s incredibly exciting because first of all, these patients are really difficult to treat, and there are a lot more of them every day,” Kosiborod said. “And until recently, we had very little to offer them, so if we know it actually modifies the disease process, we have something really effective – and by the way, really well-tolerated as well – and that’s of course great news for patients and great news for doctors taking care of patients.”

The study has some limitations. The patient population in the US was more diverse than the general US patient population, with 26% of study participants identifying as Black, but trial sites in the rest of the world weren’t as diverse, so it would be difficult to generalize these results for everyone. Researchers would also need to follow people for more than a year to see if the drug conveys lasting results.

The new research shows how important robust randomized trials are in showing that these weight loss drugs are beneficial and safe, said Dr. Naveed Sattar, a professor of cardiometabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow who was not involved in the study but who has worked on studies for companies that make weight loss drugs. “The evidence here is also mounting and reassuring,” Sattar told the Science Media Centre, a group that provides scientific perspective to the media.

“This new well conducted trial suggests once again we have underestimated the impact of excess weight in the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Preventing obesity remains critically important but newer treatments that help people living with obesity lose decent amounts of weight could help improve the lives of many living with heart failure, and many other conditions associated with obesity,” Sattar said.

Kosiborod, who presented the research Saturday at the American College of Cardiology in Atlanta, said he thinks the study also opens up an entirely new way of treating heart failure by treating obesity.

“Obesity, it is a lot more than weight. It’s a systemic cardiometabolic condition that causes all kinds of bad things, and treating obesity involves weight loss, but it means a lot more than that,” he said. “We have to target it, and I think future standards of care for this type of heart failure will improve, and without a doubt in my mind, it’s going to include obesity management.”